Why Jews Leave a Small Stone When Visiting a Grave

This article is dedicated in memory of Rabbi Michael Tayvah—friend and colleague

People often inquire as to the meaning of the Jewish custom of placing a small stone upon the headstone when visiting a grave, as in this photo of the grave of the great Israeli songwriter Naomi Shemer. Nature metaphors-- rock, stone and mountain being primary examples, are very central to Biblical interpretation. All cultures attach symbolic meaning to items that function pragmatically. Rock or stone has a relative permanence, and so is a great candidate for both functions. Jerusalem's Israel Museum has an exhibit that shows that in Biblical times, when someone died, each person present would add a stone to cover and mark the burial site. This would create a mound or reveal, in Hebrew a "gal." The family would later return to collect the bones to bring to the family cave, as well described in the story of the Cave of Machpeilah and of Joseph's bones being brought up from Egypt.

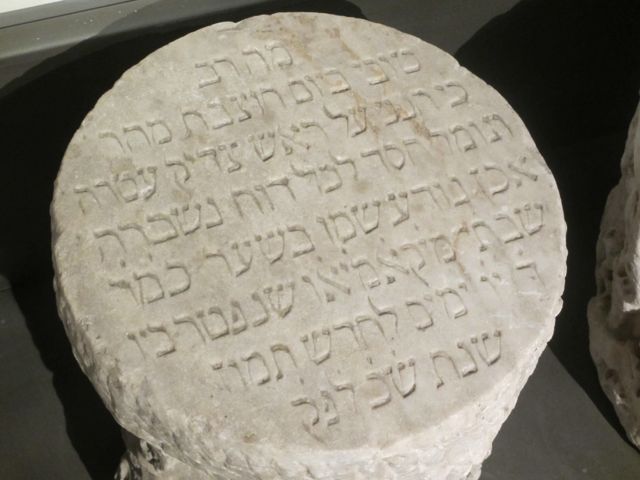

While touring Rome's Musei Capitolini the other day, there emerged a fruitful find for explaining the many metaphoric uses of stone regarding the headstone and the small stone, which we leave atop or beside it. This find was a short, round; pillar-shaped headstone that bears an entirely Hebrew inscription that translates as follows:

How great was my fortune the day I was quarried from the mountain!

How great was my fortune the day I was quarried from the mountain!

Thus, here I am, I am the crown upon the head of an honest man and I confer grace to every exhausted soul. It is for this reason his name is engraved on the door, the honorable Mr. Shabbatai Cammeo, who died the fourth day of the week (a Wednesday), the 16th of the month of Tammuz (July 20) in the year "320 computo minore" (1560 C.E.).

The Dimension of Stone and Metaphor

The Introduction to the Zohar, a foundational Jewish mystical text, provides us with the necessary analogy to advance our understanding:

The sages compared a person's soul to a rock carved off a mountain. There is no difference between the rock and the mountain, except that "It" is a whole and the rock is a part. So we must inquire: A stone carved from a mountain is separated from it by an axe; this causes separation of 'the part' from 'the whole;' but can you imagine that about 'God'?! That God will cleave off a part of God's essence--to the point that it can only be understood as a part of God's essence?

Using metaphor to comfort, connect, and restore grace, "The Mountain," represents the age-old human sense of the Unity of All Being, that we live a holographic existence, dimly, yet when reminded, actually aware we are never really apart, and that rather we are a part of "It All." This knowledge is embedded within the Hebrew word for stone itself -- eh-ven:

aleph bet nun, translates as stone. Take the first two letters--aleph bet, which in Hebrew translates as "av," (father), or parent – metaphorically the large stone, aka, the "Rock of Ages" from which has been cleaved from the bet nun "ben" (son), child, descendant, symbolized by the headstone, a soul cleaved from The Rock. Accordingly, the small stone is the symbol of your own soul as a visitor.

"The Rock" is a metaphor that functions as a portal to expanded consciousness throughout Jewish text and tradition. For example, take Jacob--on the day his name is changed to Israel, dreams upon "The Rock," which becomes a "gateway to heaven" where his destiny is revealed. He set up a matzeivah, the rock as a "monument" to the profound dream experience of his soul, where he first realizes that right there, sleeping upon The Rock that, "God was in this place, and I, I did not know!"

Moses hits out in frustration at "The Rock" when his sister, Miriam dies. The Israelites threaten to stone him to death for lack of water. So while we can peacefully remember and do honor to a soul by leaving a stone as a symbol of our visiting soul, a soul can be removed from embodied life, by stoning. For you now can see, that the metaphors are all of a piece.

Here are a few more of a great many wonderful examples. Moses is told to station himself "on The Rock," and there to chisel out two tablets made of "The Rock," and to enwomb himself within the newly created "cleft of The Rock." There, in his meditative state atop "The Mountain," he sees as though through God's eyes, and receives the revelation that will be engraved in-- stone:

This can be compared to a cave situated by the seashore into which the seas once penetrated and, having filled it, ever departed, but was always flowing in and out. So it was that God spoke to Moses and Moses to God. Midrash Exodus Rabba [45:3]

In a column of the Talmud, that birthing metaphor is also picked up:

There is a stone that has existed from the days of the first ancestors, and it is called the Stone of Nurturance. And it is three fingers larger than the earth. Why is it called the Stone of Nurturance? Rabbi Yossi said: "Because out of this stone did our world nurture itself into existence." Tosefta Yoma 2:12

The expression "three fingers" is familiar to us because it implies the cervix is readying for a human birth. How could "The Stone" (Rock) be three fingers larger than earth and yet invisible to us? A Hassidic fable recalls a man who has a lapse in his God-connection, so his rebbe reminds him of when he began to walk as a toddler his parents gradually began to let go of his overall straps and hold stand at a greater and greater distance, while still concerned for his safety.

While the phrase has become prosaic, now we can understand better the metaphor that someone is "a chip off the Old Block," and that the only enduring life insurance is that we are all "a piece of The Rock." And so, we find that God is termed the "Tzur Hevli—Rock of My [soul's] Connection (umbilical anchor) in the Adon Olam prayer that opens us to the mystery of connection to be found when we say the Shema, placing a "mezuzah" at the doorpost of our lives upon the "Threshold of Eternity."